MA// BLOG

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE HARD MEN OF FOOTBALL?

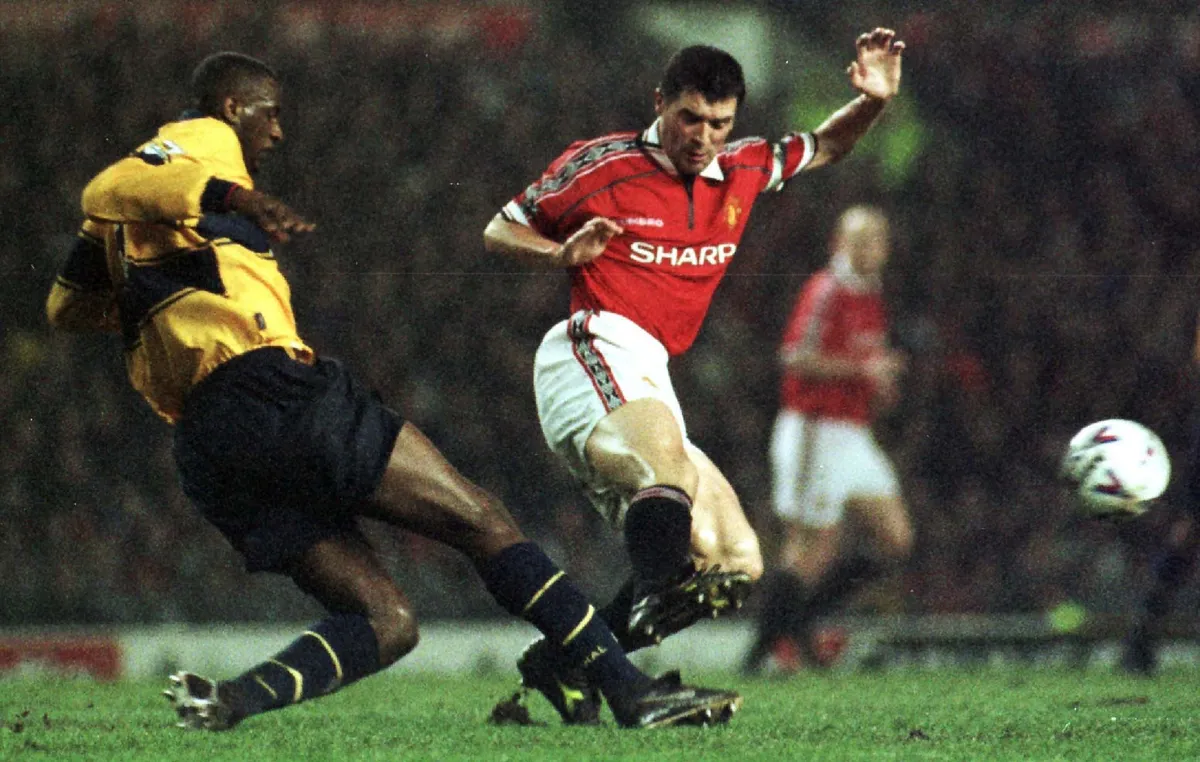

There was a time in English football when you could walk into a pub, mention the name “Duncan Ferguson” and watch grown men either grin with pride or wince in anguish. Back in Big Dunc’s day you could rattle off a first XI of hard bastards without blinking. Roy Keane staring a hole through Patrick Vieira in the tunnel. Vinnie Jones squeezing the soul out of Gazza (through his nuts). Stuart Pearce screaming into the North Bank after

a penalty like it owed him money. These were men who’d leave a boot in, eyeball the ref and headbutt a teammate in training just to sharpen up. Not just enforcers, but icons: the walking embodiment of grit, shithousery and absolute refusal to lose.

But now? Who’s the hardest player in the Premier League? Genuinely, who? Rodri? He’s got the discipline and the snarl, sure, but he’s more Ikea-functional than fearsome. Cristian Romero puts himself about, but half the time it feels like he’s just trying to get sent off. Casemiro used to be terrifying; now he looks like someone’s dad. We’ve got lads with sleeve tattoos and braided hairbands, but no one you’d want backing up if it ever gets on top at the pub. The modern game is faster, smarter, more technical and, in many ways, better to watch. But is it softer? Or is it just different?

The classic football hard man isn’t extinct, but he’s an endangered species, a relic from another time. In an age of high pressing and expected goals, there’s little room for a player whose primary stat is intimidation. But for a long time, being hard was enough. In fact, it was more than enough; it was a badge of honour.

Take Roy Keane. The ultimate midfield general. Not just because he could pass, tackle and lead – though he could do all of that in his sleep – but because he played like every game was a war he’d declared himself. Keano didn’t just beat you, he wanted to break your spirit and remind you who you were. He left careers in tatters. Look at Alf-Inge Haaland. Keane’s revenge tackle didn’t just end a match, it became a footnote in football history, the sort of thing whispered about for years. Could Keano survive in today’s game? The smart money says yes. But who would he replace in that Champs-winning PSG midfield? Would Guardiola prefer him to Rodri? And would Keano even want to play in the age of VAR?

Then there’s Vinnie Jones, a player who wasn’t just hard, but theatrically hard. He built an entire persona around it. Wimbledon’s Crazy Gang thrived on chaos, and Vinnie was their ringleader. His infamous photo with Gazza – hand clutching groin, expression like he’s ordering a pint – remains one of the most iconic (and disturbing) images in football. He had all the technical grace of a wardrobe falling down a flight of stairs, but he scared people. That was his job. He even started doing it in films.

Julian Dicks. Mick Harford. Dave Mackay. Terry Hurlock. Neil Ruddock. Men who looked like they’d arrived at training straight from a night shift at the docks. The kind of players who’d take your shin and then blame you for putting your leg there in the first place. Darren Moore, too: not just a massive presence but a calm, menacing one. A man who never needed to shout because his shoulders did the talking.

What they all had in common, beyond the crunching tackles and refusal to go down, was presence. They mattered. Even when they weren’t the best player on the pitch, they were the most felt. They were the thermostat of the team. If you were two-nil down and looking soft, these boys would be the likeliest to drag you back into it.

But football’s changed. The high press has replaced the hard press. Aggression has been channelled into data points: ball recoveries, duel success rates, counter-press triggers. The nasty stuff has been regulated, VAR’d, scrutinised by refs in high-def slow motion. Sliding tackles are rarely seen outside museums.

It’s not just the rules that have shifted. It’s the culture. Young players are brought up to think before they clatter. Academies prize composure over confrontation. In the social media age, a wild lunge becomes a meme in seconds. Brands don’t want Roy Keane. They want Jack Grealish. The hard man image doesn’t sell boots anymore, now teams are flogging pink warmup kits in their club shops. And maybe that’s a good thing.

But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t miss them. Because, for all their chaos, hard men were important. Not just tactically – though plenty of them were better players than they got credit for – but symbolically. They were the anchor points of working-class identity. They made football feel like football.

The closest we get to the modern hard man now is probably someone like Jude Bellingham or Ryan Gravenberch, not because they’re reckless or needlessly brutal, but because they play like grown men: physical, commanding, but with brains intact. These players do a similar job to your Keanos and Vinnies, but with added polish. Modern midfielders have to break up play and play the pass, to be aggressive but be cute about it.

There’s still room in football for fear, for intimidation, for presence. We just call it something else now. But deep down, every fan still loves a player who looks like they might start a fight in the tunnel. We love a bit of needle. We miss the drama. We miss the madness. So raise a pint (preferably a warm one in a plastic glass) to the dying breed. To the studs-up merchants, the silent assassins, the gravel-throated captains who’d headbutt the advertising board if it looked at them funny. The game’s moved on. But the legends remain.