MA// BLOG

ON THE BRINK: MORECAMBE, WEDNESDAY AND THE CRISIS CLUBS OF BRITISH FOOTBALL

In English football’s coastal outposts, the game can feel elemental: salt air, a sloping pitch, a club that exists as much for the town’s pride as for the league table. Morecambe FC are one of those clubs. This summer, the Shrimps were staring into the abyss. After months of unpaid bills, uncertainty over wages and an increasingly fractious fanbase, liquidation loomed. Supporters feared they might lose not just a team but a piece of Lancashire identity: the red and white shirts, the “Shrimps Live Forever” banners, the tiny Globe Arena squeezed between the bay and the main road.

Morecambe’s Near Miss

It looked like the end for Morecambe. Ownership instability left the club effectively for sale with debts mounting. HMRC had issued winding-up petitions. Staff faced the prospect of unemployment. There were genuine fears that Morecambe might follow the path of Bury – expelled from the EFL in 2019 – or Macclesfield, dissolved a year later.

Enter a lifeline: a last-minute takeover by 22 year-old entrepreneur Sarbjot Johal’s Sarb Capital, finalised just as creditors circled. It isn’t a gilded parachute – evidenced by their ongoing poor form – but it is survival. Supporters celebrated simply because they still had a badge to follow and fixtures to attend.

For outsiders, it’s tempting to shrug. Morecambe aren’t glamorous. But their disappearance would have stripped League Two of a community anchor, the away-day fish-and-chips ritual, the sense of continuity that keeps lower-league football honest. Clubs like Morecambe are the mortar in the English game’s walls: unheralded, stubbornly local, keeping everything else from collapsing.

Sheffield Wednesday’s Storm

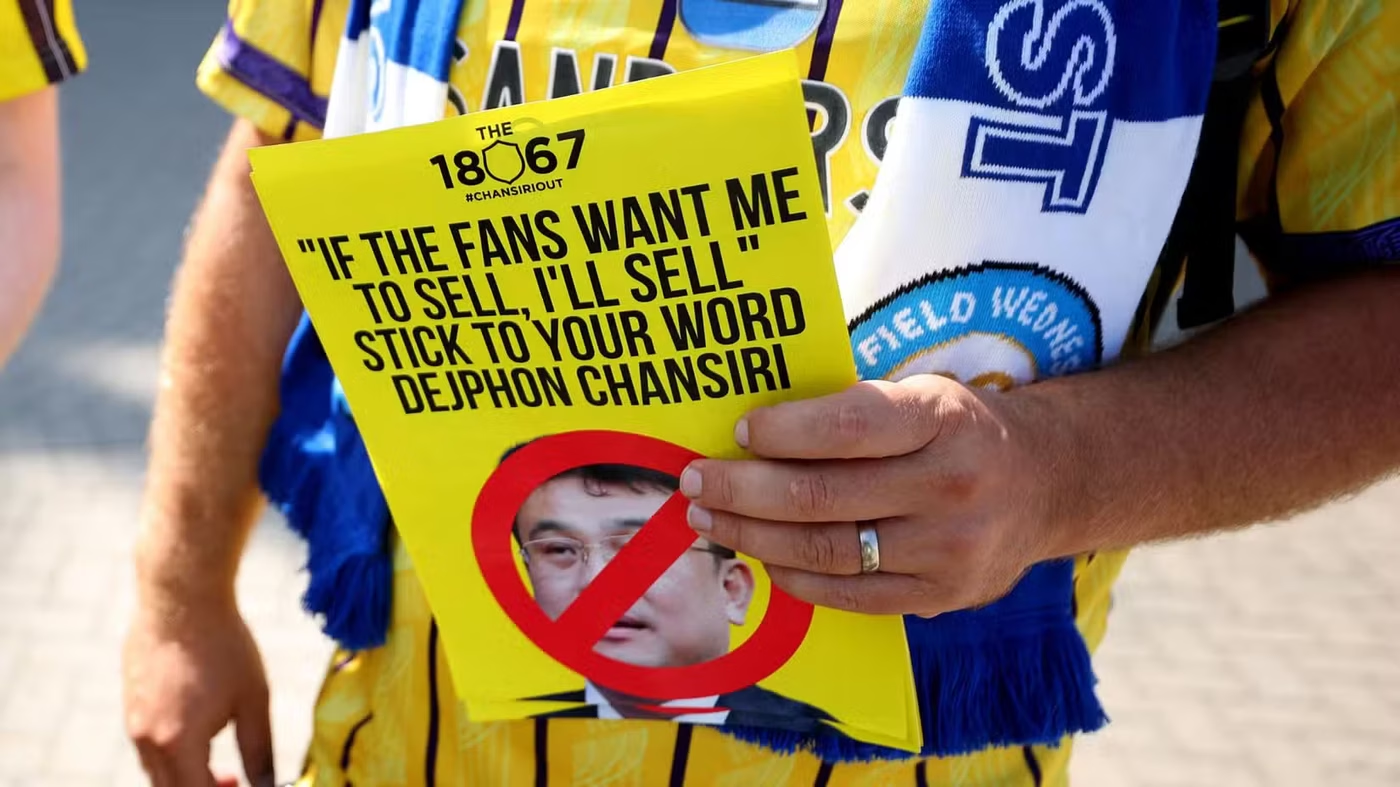

If Morecambe symbolise a rescue, Sheffield Wednesday exemplify slow-burn despair. Dejphon Chansiri’s stewardship of the club – marked by erratic decision-making, transfer embargoes, and clashes with fans – has left the Owls, historically one of England’s proudest clubs, in a bad way. Ticket prices have soared. Debt shadows the accounts. Supporters protest, yet Chansiri refuses to let go.

Wednesday aren’t staring at oblivion tomorrow, but their future looks bleak. A yo-yo existence between Championship and League One has eroded their ambition. The Hillsborough faithful crave transparency and a plan beyond simply hoping for a mid-table finish. Protests have become routine: banners outside the South Stand, chants asking Chansiri if he would please jog on. In a city where neighbours Sheffield United have recently enjoyed Premier League status (albeit short-lived), Wednesday fans feel abandoned.

This Isn’t New

Football history is littered with cautionary tales. In Scotland, Rangers’ liquidation in 2012 obliterated 140 years of continuity, forcing the club to restart in the Third Division. Portsmouth, FA Cup winners in 2008, collapsed under debt, tumbling to League Two before fan ownership managed to steady the ship.

Charlton endured the chaotic reign of Roland Duchâtelet, epitomised when the nightmare owner described fans as “customers,” prompting protests involving beach balls on the pitch. Leeds United’s “doing a Leeds” shorthand came from Peter Ridsdale’s overspending, which dragged a former Champions League semi-finalist into League One ignominy. Newcastle fans spent over a decade raging at Mike Ashley’s thrift and PR blunders, staging boycotts before the Saudi-backed takeover flipped their fortunes. West Ham’s move to the London Stadium promised a “world- class future” but delivered rows over atmosphere, ticketing and identity; the “GSB Out” banners (aimed at owners Gold, Sullivan and Brady) have flown more than once.

Lower down, Bolton, Coventry, Wigan and Derby have flirted with extinction, each crisis revealing how fine the margin is between heritage and heartbreak. Even once-stable outfits like Reading and Southend find themselves scraping survival amid unpaid wages and points deductions.

Why Are So Many Clubs Teetering?

Football’s economics remain brutally skewed. Premier League broadcast deals pump billions into the elite, inflating wages across the pyramid. Lower-league sides gamble on keeping up, overextend, and buckle when promotion doesn’t come. Owners, drawn by either romance or speculation, often lack the capital or nous to achieve long-term stability. Governance reforms have been promised repeatedly, yet oversight still lags behind the money swirling through the game.

Fan loyalty, meanwhile, is double-edged. Supporters rarely walk away, even from mismanaged clubs, which can embolden weak stewardship. Community backlash might eventually oust a regime, but usually after years of damage. In Morecambe’s case, salvation arrived hours before the shutters. Bury weren’t so lucky.

Culture at Stake

When clubs collapse, it isn’t just balance sheets that die. An entire way of life vanishes: the walk to the ground, the matchday chatter, the nicknames that have lasted generations. Entire economies of pubs, chip shops and newsagents suffer. The loss echoes beyond football: it hollows civic identity. Rangers clawed back, but ask any supporter and they’ll wince at the scars of the dark days. Charlton’s owner finally sold up, but he remains a spectral presence as owner of the club’s stadium and training ground. Worst of all: Bury’s Gigg Lane lies dormant and empty.

A Call for Vigilance

Morecambe’s survival should be celebrated, but also interrogated. How many clubs can rely on eleventh-hour benefactors? Sheffield Wednesday’s malaise is slower but no less corrosive. Governance reforms, supporter representation and sustainable wage structures aren’t romantic talking points; they’re lifelines.

Fans, for their part, keep sounding alarms, with marches at Derby, sit-ins at Blackpool and boycotts at Charlton. But emotion alone can’t offset reckless ownership. Football’s regulators must treat heritage as seriously as solvency, because history shows what’s at stake.

For now, Morecambe live to fight on while Hillsborough simmers with frustration. Yet the lesson is unambiguous: no badge, no stand, no tradition is too storied to fail. Ignore the warning signs, and the terraces may fall silent.